1st May, 2020

conspirator, radical, gossip. (an ongoing project)

as a small marker of May Day, 2020 and some attempt to share research in progress should it be of interest or use to others.

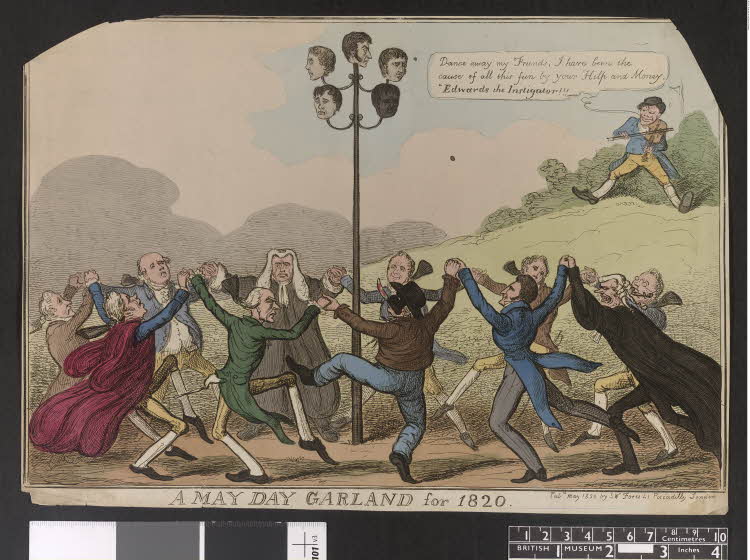

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

S W. Fores, "A May Day Garland For 1820." 1820. Print/Satirical Print, Paper. London. Prints & Drawings. The British Museum.

<<A hand-coloured etching. Ministers and others, (ten people in total) are holding hands, dancing a ring around a pole, at the top of which are symmetrically attached decollated heads. These are the heads of five Cato Street conspirators executed on 1 May 2020. In the centre foreground of the image is

a man wearing a black mask, and with a blood-stained knife in his mouth. The ten men are dancing to a fiddle, which is being played by a “Edwards the Instigator”, who can be seen in the background (right) on a grassy mound. Text in a speech bubble next to Edwards’ head reads, ‘Dance away my Friends, I have been the cause of all this fun by your Help and Money.’>>

Image description is primarily the British Museum’s own, with some minor adaptions.

Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1948-0214-837

Over the past two years I’ve been researching and developing work in response to a PhD thesis submitted to The University of Edinburgh in 1995. The thesis is titled, ‘Africans/Caribbeans in Scotland. A Socio-Geographical Study.’ and was submitted by June Evans, a Black person from Guyana who came to be living in Edinburgh and pursuing doctoral studies.1

Evan’s study spans centuries, combining archival research and documents with contemporary interviews, surveys and scholarship. The focus of my research and artworks to date have been primarily focuses on six people, figures, excerpts, mentions. At the bottom of this page are extracts that details the stories I’m currently interested in but this page has been primarily made to collate some pieces of research around William Davidson. Evan’s work introduced me to him almost two years ago, and today May 1st 2020, marks 200 years since he was killed by state. He is mentioned once, and only briefly by June, but unlike many, institutional records of his life persist, and are held in archives for his part in the Cato Street Conspiracy, a plot born following the Peterloo Massacre. Evan’s entry is follows:

William Davidson was another such Afro-Scot who came to Scotland (Fryer 1983). He was son of a Scotsman, the Attorney General of Jamaica and an African slave woman. He studied mathematics at Aberdeen University and later became a cabinet maker. Davidson was a member of a radical movement and in 1820 he became the last person in Britain to be hung, drawn and quartered (and his body thrown into quicklime) for his part in the Cato street conspiracy when radicals plotted to assassinate the cabinet (Fryer 1983).2

Throughout his trial, Davidson maintained his innocence, claiming he'd been mistaken for another man of colour in the area at the time.

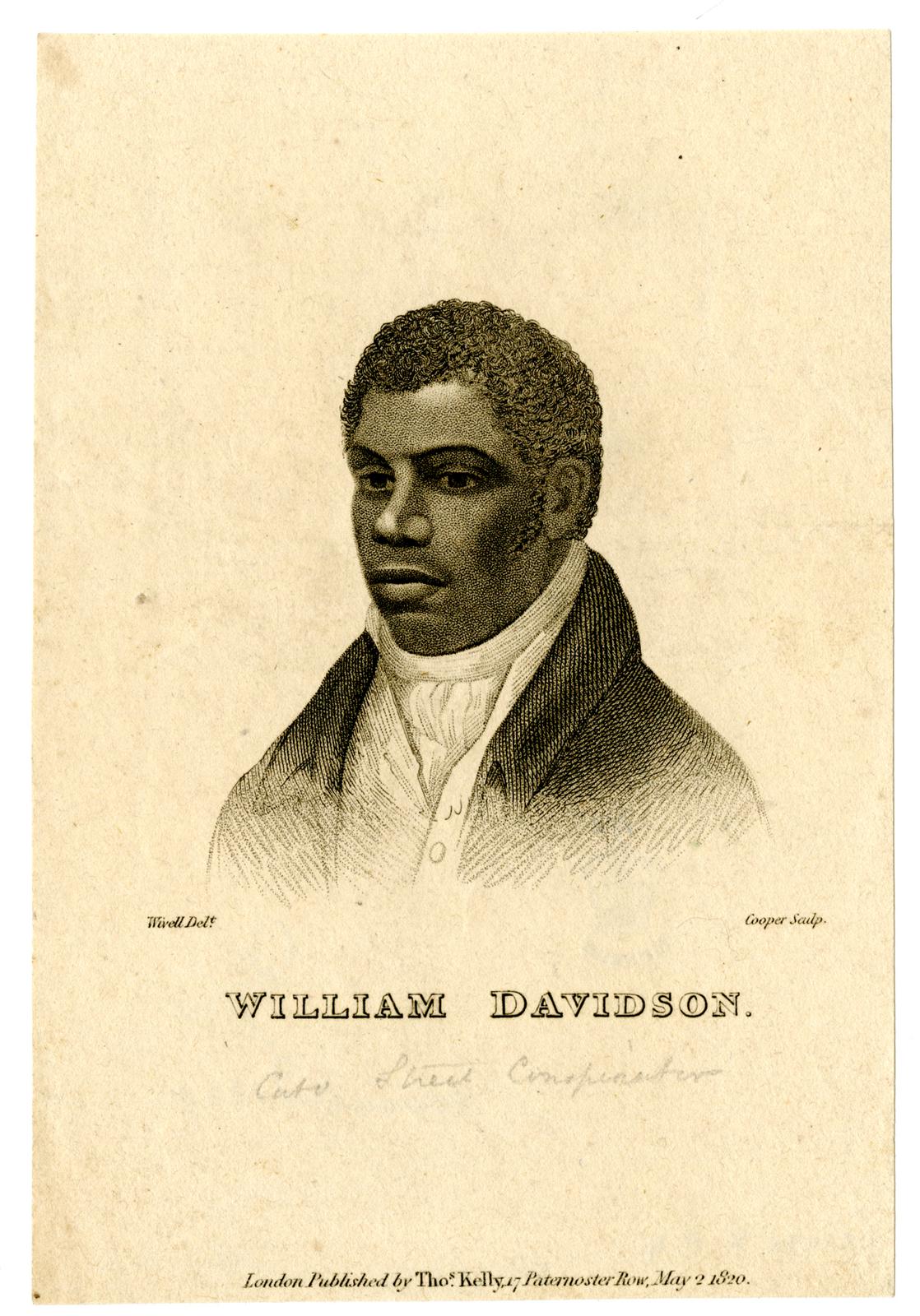

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Robert Cooper, "William Davidson", 1820. Print. London. Prints and Drawings. The British Museum.

<< A monochrome etching comprised of stipple and crayon-like marks. A portrait of William Davidson’s head and shoulders, and a inscription beneath. Davidson is looking down, his head and shoulders are turned slightly to the left. He is wearing a dark open heavy coat over light waistcoat fastened with one button and neckerchief. The prints, title, ‘William Davdison’ is just below the portrait. Beneath this in graphite is ‘Cato Street Conspirator’. The inscriptions read: 'Wivell Delt. / Cooper sculp. / London, Published by Thos. Kelly, 17 Paternoster Row, May 2 1820.' Inscribed in graphite below title 'Cato Street Conspirator'. >>Image description is primarily the British Museum’s own, with some minor adaptions.

Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1851-0308-190

Led by archival materials, rumour and gossip, I’m currently working, very slowly, as and when I can afford to, on a series of works responding to June Evan’s research intertwined with my own. [The first public sharing of work born of June’s research was screaming by citation, lol ur so drama, 2019 as part of, something vague and irrational, a collaborative exhibition with Sulaïman Majali. at Celine Gallery, Glasgow. ] As well as developing screaming by citation, I’m also working on a film and series of prints in response to Davidson’s life and death, in particular his 'eloquent and unsuccessful' speech during the trial; and his conduct on the scaffold;

Davidson ascended the scaffold with a firm step, calm deportment, and undismayed countenance. He bowed to the crowd, but his conduct altogether was equally free from the appearance of terror, and the affectation of indifference.

British Luminary and Weekly Intelligence no.84 (7th May, 1820) 146.3

Partial transcripts of Davidson’s address to the court are available online, what I find particularly interesting is that whilst maintaining his innoncence, Davidson also argues that had he taken part in the conspiracy, he would’ve been right to do so. Invoking the Magna Carta, to articulate the necessity and righteousness in resistant tyranny, King and the state. He argued that the alleged acts did not amount to treason and also that whilst witnesses point to the presence of a man of colour, none identified Davidson directly.

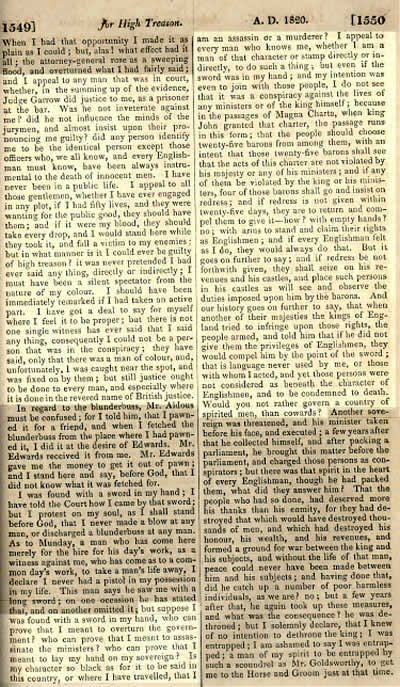

Earlier on in the development of this project, I asked friends and acquaintances to record themselves reading the available transcript for a small fee. I’m using the recordings to sketch out the shape of the future film. Below is a scan of page from Howell’s State Trials, vol. 33, cols.1549-51 (1826) featuring Davidson’s speech, the recording made by Chizu Anucha and the transcript.

Transcript:

| ...I appeal to any man that was in court, whether, in the summing up of the evidence, Judge Garrow did justice to me, as a prisoner at the bar. Was he not inveterate against me? did he not influence the minds of the jurymen, and almost insist upon their pronouncing me guilty? did any person identify me to be the identical person except those officers who, we all know, and every Englishman must know, have always been instrumental to the death of innocent men. I have never been in a public life. I appeal to all those gentlemen, whether I have ever engaged in any plot, if I had fifty lives, and they were wanting for the public good, they should have them; and if it were my blood, they should take every drop, and I would stand here while they took it, and fall a victim to my enemies; but in what manner is it I could ever be guilty of high treason? it was never pretended I had ever said any thing, directly or indirectly; I must have been a silent spectator from the nature of my colour. I should have been immediately remarked if I had taken an active part. I have got a deal to say for myself where I feel it to be proper; but there is not one single witness has ever said that I said any thing, consequently I could not be a person that was in the conspiracy; they have said, only that there was a man of colour, and, unfortunately, I was caught near the spot, and was fixed on by them; but still justice ought to be done to every man, and especially where it is done in the revered name of British justice…. …but suppose I was found with a sword in my hand, who can prove that I meant to overturn the government? who can prove that I meant to assassinate the ministers? who can prove that I meant to lay my hand on my sovereign? Is my character so black as for it to be said in this country, or where I have travelled, that I am an assassin or a murderer? I appeal to every man who knows me, whether I am a man of that character or stamp directly or indirectly, to do such a thing; but even if the sword was in my hand; and my intention was even to join with those people, I do not see that it was a conspiracy against the lives of any ministers or of the king himself; because in the passages of Magna Charta, when king John granted that charter, the passage runs in this form; that the people should choose twenty-five barons from among them, with an intent that those twenty-five barons shall see that the acts of this charter are not violated by his majesty or any of his ministers; and if any of them be violated by the king or his ministers, four of those barons shall go and insist on redress; and if redress is not given within twenty-five days, they are to return and compel them to give it – how? with empty hands? no; with arms to stand and claim their rights as Englishmen; and if every Englishman felt as I do, they would always do that. But it goes on further to say; and if redress be not forthwith given, they shall seize on his revenues and his castles, and place such persons in his castles as will see and observe the duties imposed upon him by the barons. And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their majesties the kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword; that is language never used by me, or those with whom I acted, and yet those persons were not considered as beneath the character of Englishmen, and to be condemned to death. Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? …they have come forward to swear my life away on this charge, and I now tender my life to your service; I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me, and I shall say no more... |

Documents relating to Davidson’s speech are held in the National Archives and varying transcripts can be found across the internet. Below is the partial transcript that the National Archives provide on their website, as alongside images from Howell’s State Trials, vol. 33, cols.1549-51 (1826). I presume that book has the speech in full but have not yet been able to access it.4

Film stills, screaming by citation, lol ur so drama, 2 channel film, 2019

1. The inside of an open mouth fills the frame, pink and fleshy, overlayed is a screenshot of a portrait of William Davidson. 2. Pink text over a 19th century oil painting. The painting is Scottish Landscape, 1871 by Robert S. Duncanson, a African American artist who made frequent trips to Scotland. he painting shows a river in a valley, with mountains in the background. The text reads, “I read that the last person to be hung, drawn and quarted in the british isles was a Black man.”

Further research following Evan’s lead suggests that Davidson was not the last person in the British Isles to be hung, drawn and quartered. This was the sentence delivered, instead he and his alleged co-conspirators were hung, drawn, but not quartered. Their bodies were thrown into quicklime in a passage beneath Newgate Prison where they were killed on 1 May 1820; their families had made pleas to the court, asking for the bodies to be returned to them for proper burial, this was denied.

***

Some other figures in June Evan’s research, that I’m working around at the moment/extracts of interest.

Everything italiced is a direct quote from Evans.

I. On John McIntyre who was born in Jamaica and lived in Glen Dochart, Perthsire. He studied at Dollar Academy in the 1820s and is said to have gone onto study medicine and become a successful medical practitioner.5 Referencing Bruce Baillie’s History of Dollar Academy (ND at the time, later published in 1998), an account of a racist incident at the school has stuck with me:

He remembered McIntyre because of one particular racist incident at the school whereby his German teacher shouted racist abuse at him "You are an ape, You are an ape" and Mc'Intyre responding accordingly "let his book fly at the venerable head of his enraged teacher, and hit him a good hard knock on the temple". The matter was brought up to the school board and the German teacher was dismissed. How much this act reflected the anti-racist practice of the school or the fact that McIntyre's uncle with whom he lived was the headmaster of a school and (more importantly) that his own father was a Scottish planter in the Caribbean is difficult to say.6

II. Something about dancing in the snow:

On the marriage of James VI to Anne of Denmark, Africans were still in vogue in Scotland as the celebrations for the King’s marriage was showed. Anne's journey from Denmark was disrupted in Oslo and King James sailed out there to meet her. As Antonia Fraser noted "The wedding ceremony, performed then and there, was also marred by mishap: the four negroes commissioned by James to dance artistically in the snow, all subsequently perished of pneumonia" (Fraser 1974: 52,53). 7

III. The cold forced him to move to France where he died. Writing on Charles Heddle, the “African Merchant Prince” in Scotland in the 19th Century.8

IV. …the 1919 court case of Cornelius Johnstone who was charged with keeping a public dance in Glasgow without a licence (Jenkinson 1985 : 64). It takes a criminal offence to provide a glimpse of this hidden group enjoying forms of their own social and cultural life with "premises" rented for the purpose of a "coloured man’s club”. That the place was packed with dancers suggests other African people present.9

V. Kirsty Sanderson who reminds me of the wayward, anarchic and riotous Black girls written about by Hartman and others. She was born in Leith some time in the 19th century. Kirsty made part of her living as a washer woman. One night, with the help of good friends, she lured a man into a house, got him drunk and robbed him. She was shipped to Australia for said crime.10

1. Use of ‘came to’ here only serves to indicate the limited biographical information I have relating June Evans, all of which comes from the PhD thesis. Further investigations into Evan’s life, (before I began to think about the ethics of the endeavour) led to similar responses, people remember speaking to June when they were conducting their research, but no one seems to know what they did next. The PhD can be accessed here, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/7187

2. June Evans, “Africans/Caribbeans in Scotland. A Socio-Geographical Study” (PhD diss. The University of Edinburgh, 1995), p 78.

3. Peter, Fryer, Staying Power: The History Of Black People In Britain. (London: Pluto Press, 1984), 219. See also "William Davidson”, Spartacus Educational, https://spartacus-educational.com/PRdavidson.htm.

4."Black History | Rights | The Cato Street Conspiracy”, National Archives, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/cato.htm.

5. Daniel Livesay, Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain And The Atlantic Family (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018) , 357. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/57406.

6. Evans, June, 1995, p. 77.

7. Evans, June, 1995, p. 126.

8. Evans, June, 1995, p. 78.

9. Evans, June, 1995, p. 191.

10. Evans, June, 1995, p. 78.